"A couple with a child in between them. A very young girl and a parent on the floor next to her. A man in his 20s or 30s. An older woman slumped in a booth. Two teen-age boys in T-shirts and shorts with their dinners still half-eaten on the table.

"I have a churning stomach. It looked like a war zone." -Roger Hedgecock, mayor of San Diego after seeing the massacre site on July 18, 1984

About two miles north of the Mexican border we exit the San Diego Freeway, and follow the blue road-side sign toward McDonald's franchise #7382. On top of the restaurant built in 1984 to replace the razed slaughterhouse down the street, is a 25-foot-tall inflatable Ronald McDonald.

He sits cross-legged like Buddha and gives a toothy smile that could only come with enlightenment.

Few people would travel over 200 miles in a day to see a corporate burger joint, much less a former site of one. Of course, most people wouldn't visit findagrave.com to plan their vacations. And this was no ordinary McDonald's, either.

Instead of going to a Padres game or the zoo like normal people do, there was another place I wanted to see in "America's Finest City." And it's not the sort of sites you'll find in a Frommers' Guide.

My destination is the location of one of the worst shooting sprees in American history -- the San Ysidro McDonald's massacre. We pull up to the stop light at 484 San Ysidro Boulevard next to the white marble edifice that before July 18, 1984, was just another place to get a Big Mac and a Coke. But thanks to the actions of one gun-obsessed, unemployed security guard, the Golden Arches have been replaced with a community college building billed as a "living memorial."

We park at the San Ysidro Post Office, next door to the killing field. Here, 26 years earlier, a police sniper finally ended a gunman's 77-minute rampage with a single shot from the post-office roof. The building's north side is still scarred from the bullets fired that day from inside the McDonald's, where scores of customers and employees were shot, and 22 people perished.

In front of the two-story Southwestern Community College Education Center, I see a Jack in the Box sandwich wrapper lying next to twenty-one hexagon pillars, one for each victim discounting the killer. Crumpled McCafe cups litter the memorial, just a small cup of coffee away from the replacement McDonald's down the street. I can't help but think that these victims were ripped off in the monument department.

At Bath, Mich., a park and museum are dedicated to the darkest day in the town's history, when Andrew Kehoe blew up the Bath Consolidated School in 1927. A large bronze statue in the center of a fountain graces the Edmond Post Office in Oklahoma, where Pat Sherrill murdered 14 of his coworkers in 1986. And the Columbine Memorial in Littleton, Col., receives visitors and upkeep on a daily basis.

But in southern San Diego, the tribute to the victims of the San Ysidro McDonald's massacre attracts little attention. A metal fence, about four-feet high, prevents hyper children from using the memorial as a playground while their apathetic parents wait for the bus. Students in their 20s race to class across the spot where 11-year-old Omarr Hernandez lay bloody and hemorrhaging. The understated plaque beside the white marble memorial contains no reference to the massacre, and the name of the college is etched with a larger font than that accorded the names of the victims.

On the opposite side of town, the crypt of McDonald's founder Roy Kroc bears an equally boring and uninformative plaque in El Camino Memorial Park. On January 14, 1984, the day Kroc died of heart failure, another man who would bring national attention to the company -- James Huberty -- was moving his family to the area. They would eventually settle in the southernmost part of Kroc's home town, half a block away from the site where James would make food, folks and fun inseparable from gore, guts and guns.

James Oliver Huberty was born in Canton, Ohio, on Oct. 11, 1942. Throughout his life he walked with a slight limp brought about by polio he contracted when he was 3-years old. Disease wasn't the only hardship for James as a child. In the early 1950s his father Earl bought a farm in Ohio's Amish country, with plans of moving the family there. His mother, who abhorred the idea of living among Mennonite farmers, left the family to become a street preacher on the Southern Baptist circuit. Earl's father worked the late work shift, and spent little time with his son. Having no mother, a father who was barely around, and bearing the social stigma of having divorced parents, James had few close childhood relationships. He stayed inward and withdrawn throughout most of his adolescence.

After receiving a sociology degree at a Jesuit college in western Pennsylvania, James enrolled in the Pittsburgh Institute of Mortuary Science. There he met his future wife Etna. The couple married in 1965 and had two children, Zelia and Cassandra.

Until 1971 the family lived in Massillon, Ohio, where James apprenticed at the Don Williams Funeral Home as an undertaker. If mourners would stay longer than usual visiting hours, James was known to pace back and forth muttering "Get out." If that didn't work, he would start turning the lights off.

Within three months James was fired for misconduct. And when their home caught fire, the family was forced to move. Back in Canton, the family made ends meet from renting out a six-unit apartment house, supplemented by James' work as a welder for Babcock and Wilcox.

Neighbors in Canton always thought that Huberty would snap. Most would say in interviews that they were just glad that he didn't do it there. James, a survivalist, anticipated any number of scenarios for the downfall of America ranging from economic collapse, to all-out nuclear war with the Soviet Union.

James secured massive amounts of non-perishable food, six guns, and enough ammunition for the family to hold their own against the chaos that was to come. While well prepared for a kill-or-be-killed Darwinian future, the family didn't fit well into Jimmy Carter's middle class. Neighbors would get used to sudden bursts of gunfire from the family's basement, where James had set up a make-shift shooting range.

At one point, a neighbor complained that the Huberty's German Shepherd had damaged his car. James told the neighbor he would take care of the situation. He took the dog to the backyard, and shot it in the head. When the neighbor, abhorred by such an overreaction to a trivial incident, talked to him about it, James responded: "I believe in paying my debts, both good and bad."

On another occasion at a neighbor's birthday party, Etna told her daughter, Zelia, to assault a fellow classmate in retaliation for a perceived slight. When later confronted by the angry mother, Etna threatened the woman with a Browning Hi-Power 9 mm pistol. Etna was put in jail for the weekend, but she and the gun would be released by the Canton Police to her husband's custody. It was one of the three weapons he would take with him on his killing spree.

Most absurdly, in an act that would today get you tried under terrorism charges, James would jokingly step out on his front porch with a rifle, aim at his neighbors, laugh heartily, and return inside.

The aggressive behavior wasn't limited to neighbors. Etna said in an interview that the family once had to remodel their kitchen because she had attacked her husband so fiercely with a broken table leg during a fight. On another occasion she filed a report with the Canton Department of Children and Family Services because James had "messed up" her jaw. She would occasionally try to quell his temper by pretending to read his future with a deck of tarot cards, spewing nonsense about fame, or economic security.

In 1983 Babcock and Wilcox closed its Canton factory due to the recession, putting James out of work. Left with no safety net or pension, James became more openly bitter and angry. At one point after being laid off, James sat in the family's living room with a silver revolver to his right temple. Etna struggled to pull the gun away from him, and convinced him to rethink the decision.

Believing things to be better outside of the United States, the family moved to Mexico. The non-perishable food was left to gather dust at the house in Canton, but James made sure to take the guns and ammunition. Within a year one of the guns would be photographed in Time magazine next to a discarded hamburger patty.

After a brief stay in Tijuana, the Hubertys settled in the mostly Mexican community of San Ysidro. They lived in a house on Cottonwood Road before moving into a modest apartment complex called Averil Villas. The family's new home sat about the length of a football field to the East of the smiling, fiberglass McDonaldland characters that enticed children into the Playplace.

The family's hopes for a better future on the West coast were as quickly crushed as a fast-food-workers' union. After turning in applications to multiple firms, James eventually found work as an armed security guard for a San Diego condo complex. Although once again employed, James hated the new city. Day-to-day, petty grievances became all the more irritating. Several days before he would shoot 40 people, he complained to his wife about how the ice cream machine at the McDonald's down the street was still broken.

Etna was surprised by James' behavior on July 17, 1984. Although fired from his security guard job two weeks earlier, he wasn't his usual doom-and-gloom self. And he called the San Ysidro Health Center seeking help for his anger issues.

Due to a misinterpretation over the phone, James was listed as "J. Shouberty." His call was never returned. The mental health clinic would have to explain this mistake over and over during the ensuing months of media attention.

That evening the couple watched a movie together on the couch. James got up to make a snack to share with his wife. She went to sleep hopeful that some of the family's troubles may have reached a catharsis.

The next morning, things continued to look up when the Huberty family went to the San Diego Zoo. But, as Zelia and Cassandra gawked at pandas and elephants, James vented to his wife about the state of the world. He told her that "Society had its chance." Afterward, they stopped for lunch at a McDonald's in northern San Diego. James had Chicken McNuggets, fries, and a Coke.

Back at the apartment, Jim went to the master bedroom as Etna cleaned neglected dishes. Cassandra went to a neighbor's house to babysit. Zelia told her mother that her father was messing around with some ammunition, a statement that caused no alarm in the gun-owning family.

Seeing the master bedroom door closed, Etna laid down on a daughter's bed to rest. James came to the doorway telling his wife that he wanted to kiss her good-bye. He then said he was going "hunting humans," gave her a double thumbs up, and left.

Thinking nothing of what she considered to be her husband's dark humor, Etna and Zelia soon headed out to run errands. By the time they headed back from Safeway, the Freeway and roads around their apartment were closed. The two went to get Cassandra who was babysitting, hoping to keep her a safe distance from McDonald's, where gunshots rang out and customers inside screamed for their lives.

Etna, to her horror, saw a Mercury Marquis exactly like their own sitting in the restaurant's parking lot. She became terrified when she read the car's bumper sticker, and sealed the connection. "I'm not deaf -- I'm ignoring you." After picking up Cassandra, the family waited anxiously for the official identification of the gunman, although they were pretty sure who it was.

Twenty minutes earlier, as the Democratic Convention continued in San Francisco and organizers tied up final strings for the Olympics in Los Angeles, James took a right turn out of Averil Villa prepared to shock the world. He had the weapons; all he needed was the venue.

Before determining that McDonald's would yield the highest body count, James was seen checking out the U.S. Post Office and the local Big Bear Supermarket. Shortly before 4 p.m. he drove the black family sedan past the red and yellow sign proudly proclaiming "over 45 billion served." He entered the McDonald's with an Uzi carbine and a 12-ga. Winchester 1200 shotgun slung over his shoulders. The Browning HP tucked in his belt rounded out the arsenal.

James screamed for everybody to get down near the front counter, and then began shooting diners and employees at point-blank range. Blood splattered victims fell to the ground clutching hamburgers, McNuggets and serving trays as James fired round after round into customers and employees alike. He carried enough ammunition to kill everybody in the restaurant and to hold off police for several hours.

Dozens of people bled, cried and prayed as they laid helplessly beneath the tables. If they moved, James would shoot. If they stayed still, James would shoot. Families, playing dead under tables, discreetly tried to patch up their wounds with logoed napkins as if blood were ketchup.

Josh Coleman, David Flores, and Omarr Hernandez were heading out to get a patch for a bike tire and some doughnuts shortly before James opened fire. Sweet tooths still unfulfilled after their Yum Yum Donuts trip, the preteens biked to the McDonald's, just two buildings away, for ice cream and a Coke. As they approached the doors, a man across the street shouted for them to get away. Too late.

Omarr and David died at the scene, as Josh played dead. He would keep conscious by singing songs to himself until the gunman was down, and police converged on the restaurant. A photo of Hernandez, face-down on the sidewalk, corporate logos in the background, would come to symbolize the massacre on newspaper covers across the globe.

Although police received calls about a shooting at a McDonald's within minutes, emergency vehicles were mistakenly dispatched to the restaurant on the U.S./Mexican border two miles south of San Ysidro. Precious moments were lost as James bent to his gruesome task.

Miguel Rosario, believing he was responding to an accidental shooting, was the first police officer at the actual scene. Patrons were hiding behind cars throughout the parking lot when he arrived; others ducked behind the low walls of the McDonaldland Playplace. James came to the side door, Uzi across his chest, and fired nearly 30 rounds at the officer.

Rosario, armed with only a .38-caliber revolver, knew immediately that he was out-gunned. Shielded by a truck, he called in a Code 10- "send SWAT team," reconsidered, then called in a Code 11- "send everybody." Within the next hour, 175 police officers would surround the building as Huberty continued to gun diners down.

As news helicopters hovered, and police took tactical positions, the fast food restaurant was beginning to look more like a war zone than a symbol of American commerce. Traffic stretched back for miles on both sides of the closed San Diego/Tijuana border. By 4:35 p.m. the first SWAT team arrived to relieve officers on the north side of the building, but neutralizing the gunman would be more difficult than expected. The glare from the sun in the shattered windows made it impossible for snipers to get a clear shot.

SWAT teams today are designed with these kinds of events in mind, but in 1984 they consisted merely of regular police officers with additional training and special equipment in their squad cars. Lack of accurate information on the number of gunmen, their weapons, and the state of survivors made police decisions more difficult. Confused reports from traumatized witnesses further exasperated the situation.

Inside the restaurant, James was working up quite a thirst. He jumped over the counter and helped himself to a paper cup and the Coca-Cola dispenser. He took a couple of sips before throwing the cup, as well as derelict hamburgers and fries, at the corpses lying in his vicinity.

At some point in the rampage, James found a portable radio that belonged to one of the workers. He changed the station multiple times in search of the right station. Employees, hiding in the back, believed that the gunman turned it on to hear news of his exploits.

Between firing rounds into more victims, and reloading his guns, James would break out into an improvised jig. Injured victims reported hearing Michael Jackson music in the background of the gunshots, and James screaming and yelling obscenities.

At Around 5:00 p.m. a second SWAT sniper team was set up on the roof of the Post Office immediately next to the drive-thru lane on the south side of the restaurant. Police, by this point, had confirmed that there was only one gunman armed with multiple weapons. It was also determined that more than a dozen people were still inside; how many of them were still alive was unknown.

At 5:13 p.m., SWAT Commander Lt. Jerry Sanders arrived at the scene, and gave the "green light" for shoot to kill orders. James continued firing through the Golden Arch-imprinted window at the front of the restaurant, now aiming at the men, women and children gathered to watch his spectacle unfold. A SWAT officer on the ground floor of the post office fired two shots, drawing return fire from James.

On the roof of the post office Chuck Foster focused the scope of his Remington .308-caliber rifle on James' maroon veneer shirt, right above his heart. At 5:17 he fired a single shot from a distance of about one hundred feet, killing James instantly. It was one of only five shots fired by officers during the entire incident.

In today's cultural environment, spree shootings are about as American as MSG-enhanced, artificially flavored McDonald's apple pie. In 1984 though, the thought of someone opening fire on a group of strangers seemed about as likely as someone crashing airplanes into the Twin Towers. The closest event remotely comparable to this at the time was Charles Whitman's sniper attack from the University of Texas clock tower 18 years earlier.

Throughout the next decade, the number of rampage attacks would grow exponentially. Like an Eric Harris or Dylan Klebold of the 1980s, James Oliver Huberty became a martyr to disenfranchised, me-against-society, gun-owning loners across the nation.

A year after Saint Jim's massacre, a 25-year-old woman in Springfield, Pa. walked into a local McDonald's, hand raised in a mimed gun, and said "I'm going to blow you all away." Sylvia Seegrist was an unemployed paranoid schizophrenic who spent a lot of time hanging out at the local mall. Patrons and employees alike knew her for her harassment of customers and bizarre monologues.

The usual subject of Sylvia's rants was James Huberty, and how "good" his particular rampage was. On the afternoon before Halloween in 1985, Sylvia arrived at Springfield Mall dressed like a commando. She got out of her Datsun B-210 carrying a Ruger Mini-14 and immediately began firing at a woman using an ATM machine.

For four minutes, Sylvia lived out her commando fantasy, killing three and injuring seven. John Laufer, a shopper, thought that the shootings were nothing worse than a very offensive pre-Mischief Night prank. As Sylvia raised her semi-automatic carbine at him, John disarmed Sylvia of what he believed to be a toy gun.

Sylvia sat awkwardly in a shoe store, like a 15-year-old caught shoplifting, as Laufer retrieved a security guard. While being escorted from the mall into police custody, she said "What happened in California was good. It should happen again."

Sylvia's first victim was 2-year-old Recife Cosman, shot in the heart and lung. The Cosman family was waiting for a table at the Magic Pan restaurant just inside the mall's entrance. The newspaper images of blood stains on a restaurant floor and walls covered by bullet-pocked corporate logos conjured up memories of the previous summer in south San Diego.

Sylvia, charged with three counts of murder and seven counts of attempted murder, was found guilty but insane. She's incarcerated at a state correctional facility in Muncy, PA. Unlike James, Sylvia had a history of delusions, and had been institutionalized multiple times. While she may not have attacked in the same mindset as James, the slaughter in San Diego had no doubt left an impression.

In Belton, Texas, George Hennard considered James Huberty to be his role model. While kicking back beers or smoking joints with his band mates, he would recount the McDonald's massacre play-by-play, as if it were a football game. At one point, most likely while he was with the Merchant Marine in San Diego, "Jo Jo" made a pilgrimage to 484 San Ysidro Boulevard. Among the items police would catalog as evidence at his house would be a VHS copy of a documentary about Huberty.

On October 16, 1991, George smashed his cherished blue 1987 Ford Ranger pickup truck through the floor-to-ceiling windows of the Luby's Cafeteria in Killeen, Texas, then followed in his role model's footsteps. With a Ruger P89 and a Glock 17, George murdered 23 diners and injured 20 others during the afternoon rush on Take Your Boss to Lunch Day. The shooting lasted shortly over six minutes before police managed to corner Hennard in the bathroom alcove.

After being injured in a shootout, Hennard killed himself with a bullet through the head. The physical and psychological wounds left by Hennard's rampage shocked an America that by now was well acquainted with workplace rampages and mass killings.

With two more fatalities than in San Ysidro, the Luby's Massacre took the rank of first place in America's spree-shooting history. It would hold that spot until Seung-Hui Cho killed 32 at Virginia Tech University in 2007. When George crashed through the front of the cafeteria and started shooting, a witness in the parking lot's first thought was, "Oh my God, it's another McDonald's!"

As soon as police sniper Chuck Foster took his shot at San Ysidro, police charged the restaurant. Seventeen cooling bodies, including the corpse of James, sprawled on the floor and slumped in booths throughout the building. Four more victims lay outside. Another would die in the hospital.

Nineteen of the luckier victims would recover from buckshot and bullet wounds. The dead and wounded ranged from 6 months to 74 years in age. Of the 47 people at the restaurant at the start of the spree, only three employees, a woman, and her baby, all of whom hid in the basement, left unscathed.

As afternoon turned into evening, America's favorite place to get a burger was transformed from a slaughterhouse into a temporary morgue. Sheets as yellow as Ronald's jumpsuit were placed over the bodies, and pools of coagulated blood seeped through the material in a macabre parody of the company's colors.

With the smell of gunpowder and hamburger grease still thick in the air, Chaplain William Mooney of the San Diego Fire Department stepped around the sheets, administering last rites for the deceased. Local funeral parlors, overwhelmed by the number of victims, used the San Ysidro Civic Center to hold wakes. Our Lady of Mount Carmel Roman Catholic Church held back-to-back funeral masses to accommodate the dead.

In the aftermath of the massacre, the San Diego Police Department made drastic changes to its SWAT team program, and the way it deals with active gunmen. Police in other cities followed suit with better weapons, equipment and continuous training.

Living victims and relatives of the dead sued McDonald's and the franchisee for failing to offer proper protection in a San Diego Superior Court. In 1987, a California Court of Appeals would find for the defendants on the grounds that they had no duty to protect customers from an unforeseen attack, and because no security deterrents would have stopped a gunman with no regard for his own life.

In 1986, Etna Huberty sued the McDonald's Corporation and her husband's former employer, Babcock and Wilcox, for nearly $5 million in an Ohio state court. Scientists who did an autopsy found disturbingly high levels of cadmium and lead in Jim's body. Etna believed the combination of constantly inhaling poisonous metals during his work as a welder and the mono-sodium glutamate in Chicken McNuggets was responsible for bringing about delusions and rage that lead to the shooting. The court would find in favor of the defendants.

Pulling out of the post office parking lot, we take a left towards McDonald's franchise #7382. All of this thinking about spree shootings in restaurants has me hungry. While waiting in line, I look around the restaurant, and reflect on how we deal with tragedy in McWorld.

When someone commits mass murder, the logical business decision is to raze the building, erect another down the street, and go on as if nothing has happened. I can attest that lower-class families still mindlessly chomp burgers in the replacement restaurant, just like they would have a block south of here a quarter century ago. The customers don't know or don't care about Huberty's rampage, the same way they don't know or care about crushed labor unions, employee sexual harassment, or the slaughterhouses that their burgers and McNuggets come from.

This is American apathy at its finest. This McDonald's, not the college building or the meager monument, is the true "living memorial" to the San Ysidro McDonald's massacre. A poorly paid Mexican immigrant hands over my french fries and Happy Meal toy. Pulling away from the inflatable, waving Ronald McDonald, we drive past the memorial one last time.

I shove another perfectly shaped, machine-cut fry into my mouth, thinking about Robbie Hawkins. Before murdering eight people at Westroads Mall in Omaha, Neb., Robbie slaved away for 15 cents above minimum wage at McDonald's. When he was fired for allegedly stealing $13 from the register, he opted for infamy instead of another low-paying service industry job.

Another shooting spree. Another media scrum. Another martyr. And one more perfectly shaped, machine-cut fry from a grease stained bag with the ironic slogan: "I'm loving it."

All of our Serial Killer Magazines and books are massive, perfect bound editions. These are not the kind of flimsy magazines or tiny paperback novels that you are accustomed to. These are more like giant, professionally produced graphic novels.

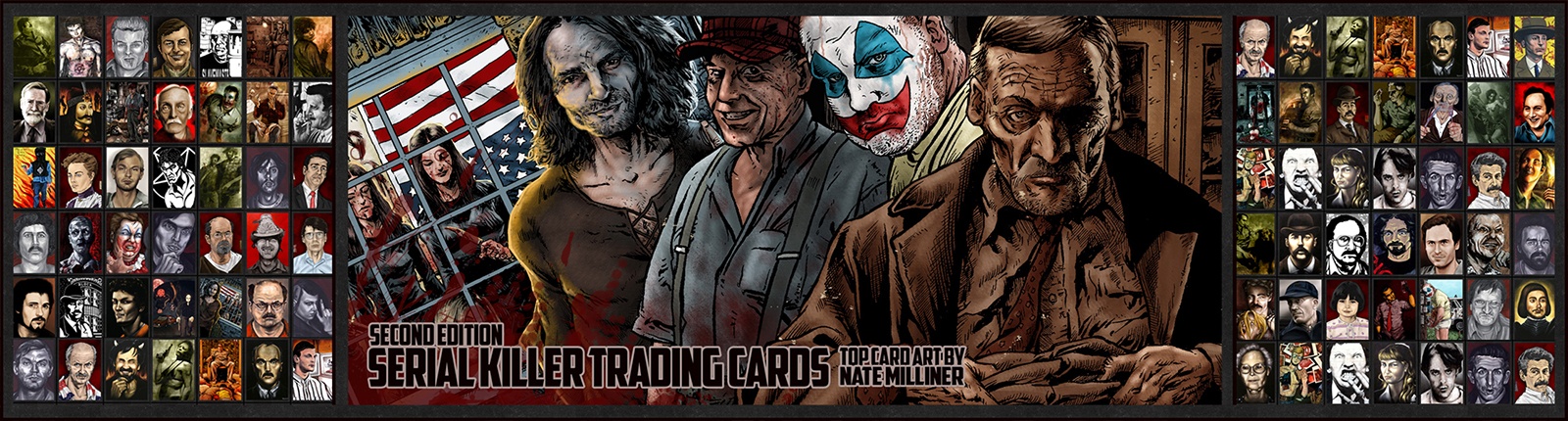

We are happy to say that the Serial Killer Trading Cards are back! This 90 card set features the artwork of 15 noted true crime artists and will come with a numbered, signed certificate of authenticity for each set. get yours now before they are gone forever.

SERIAL KILLER MAGAZINE is an official release of the talented artists and writers at SerialKillerCalendar.com. It is chock full of artwork, rare documents, FBI files and in depth articles regarding serial murder. It is also packed with unusual trivia, exclusive interviews with the both killers and experts in the field and more information that any other resource available to date. Although the magazine takes this subject very seriously and in no way attempts to glorify the crimes describe in it, it also provides a unique collection of rare treats (including mini biographical comics, crossword puzzles and trivia quizzes). This is truly a one of a kind collectors item for anyone interested in the macabre world of true crime, prison art or the strange world of murderabelia.

All of our Serial Killer books are massive, 8.5" x 11" perfect bound editions. These are not the kind of tiny paperback novels that you are accustomed to. These are more like giant, professionally produced graphic novels.

We are now looking for artists, writers and interviewers to take part in the world famous Serial Killer Magazine. If you are interested in joining our team, contact us at MADHATTERDESIGN@GMAIL.COM